Wake Island: Exploring the Imagery, Sickness, and Energy of 2025: March

March Edition

New dispatches, curated and written by David Leo Rice and Paul K, are released on the first of every month throughout 2025.

Check out our podcast: WAKE ISLAND—a conversation series exploring the darkening undercurrents of contemporary culture. 🕳️🐇

“Wow… Everything’s computer.” Donald Trump

“I am become meme.” Elon Musk

One of the strangest convergences in the culture this spring is that the anti-tech, pro-human feeling that has been percolating at least since 2024, the yearning toward a New Romanticism or a “Post Social Media Age,” that was part of the force that propelled Trump back to power — the yearning for a clearly human, flawed, impulsive, willful personality in the big chair, after the amorphous, mumbling, committee-approved absence at the center of the Biden years — has merged with the backlash to the new Trump coalition, a refusal to accede to a new ruling class of social media tycoons and crypto grifters.

Thus, the “New Humanism” transcends the obvious divides, taking on a nationalistic and even fascistic dimension in some applications, and a radically humanistic dimension in others (and in some cases this divide breaks down too). What unifies these vectors is the desire, perhaps as a last gasp, as a “too little too late” final stand, to insist on the primacy of the human body and the human mind in the face of forces that want to obliterate and commodify both.

For myself, I feel increasingly drawn to smaller and deeper communities, forsaking the wide-open sea of the Twitter feed that dominated the discourse of Trump 1.0 and the Biden years. Now, my focus is on reading books, talking with friends and family, and reading and writing here, on Substack. I don’t think this is just a matter of migrating from one platform to another — it’s the shift from reading thousands of ephemeral, random opinions every day to reading the lengthy, rambling, obsessive thoughts of at most a dozen people. It’s a much smaller sample size, a deliberate ignorance of “the larger conversation,” and therefore an insistence on returning to patterns and flows of thought that feel natural and sane, away from the nauseating yet addictive desire to always “know what’s going on” that Twitter in its heyday preyed upon. If for nothing else, I thank Elon for making that site so shitty that (mostly) leaving it behind has at last become possible.

Perhaps this is tied to the death of the spurious ideal of “multitasking.” All through the 2010s and early 2020s, people assumed, on a very basic level, that they had to watch and listen to and read as much as humanly possible, no matter how shallowly (hence the vogue of listening to podcasts and audiobooks on 1.5x or 2x speed, while at the gym or washing dishes, etc etc…). It was a gluttonous, joyless time of packing in as much as possible, of binge-watching supposedly important TV not out of any joy or even desire but out of a sense of obligation. Art and entertainment became “content to get through,” as did the news and everyone’s takes on that news and the new news about those takes, and on and on forever, until the point of total exhaustion which has now, thankfully, begun to arrive. As people felt less and less able to affect the course of events in a direct way, the need to track and critique and critique others’ critiques of those events became the only action that still felt within reach, but now even this drive, for better and for worse, is reaching its exhaustion point.

In the past decade, when I saw lists of the best books or movies or albums of the year, I felt the dread of a student being given an insurmountable homework assignment, as if some unseen force were compelling me to absorb all this media by a certain deadline, to hastily check it off and keep moving. Now, I feel none of that. If I see such a list — and I seek them out less and less often — I might pick one or two titles that intrigue me and leave it at that. I feel saner than I have in a long time.

***

This turn toward smaller, deeper conversations and away from the need to follow “the whole story,” or even to believe there is any whole story, is bound up with an encouraging return to auto-didacticism and alternative schooling models, of salvaging the humanities on new ground, not resurrecting them in the halls of the elite colleges where they died. While Trump’s attacks on elite colleges are certainly disturbing and deserving of protest in some cases, no one can deny that something has been very wrong with these institutions for a long time. They’ve stopped taking themselves and their students seriously and have abandoned all disciplines outside of tech and perhaps some hard sciences (though these seem pretty corrupted too), leaving a void that is filled, on the one hand, by laziness and idiocy and AI—or by rank careerism poorly masked as social engagement —and yet also, thankfully, by an increasing flourishing of alternative means of taking yourself and your peers seriously and drilling into literature, art, history, and philosophy with a clarity and sincerity of intention that these mega-schools no longer permit. Whether this is through podcasts, YouTube channels, Substacks, private seminars in person or on Zoom, or actual alternative educational institutions, there’s a feeling in the air that we’re finally free to leave the dead institutions behind and that this does not at all require leaving behind the actual processes of teaching and learning that are so valuable to the basic project of human society, and the basic health of imagination and inner life.

This all feels like a new form of freedom from old established orders, a freedom that Trump may have nothing to do with, and that he may actually oppose, and yet this shift is undeniably bound up with the larger feeling of this era that has propelled him back to power (even as disenchantment with his new reign sets in).

***

“The singularity need not be a purely technological event.” Yanis Veroufakis makes this argument in his compelling new book, Techno-Feudalism: What Killed Capitalism, an Adam Curtis-esque exploration of the underlying history of the 20th and early 21st centuries, culminating in an argument that we are entering a new era of world history now, one in which the Hollywood image of “the singularity” requiring technology to become fully sentient and autonomous is misleading. Rather, he argues, the singularity we’re experiencing now is a new kind of power made possible by the merger of a very few human actors, like Musk, with vast and new forms of technological power over entire populations. The technology — whatever “AI” comes to mean in the next few years — need not think for itself in order to mark a decisive shift away from the power structures that governed the world up through the 2010s.

If so, then these smaller communities of reading and writing together, for free or with very little money changing hands, are all the more crucial, even in their futility against the larger forces in play.

The return of the ancient acceptance that mind and body are not separate and not separable—just as consciousness is perhaps not separable from matter, making it a fundamental rather than an emergent property of the universe—is part of the return to the understanding that we are part of nature and part of history, not at the end or outside of either… a terrifying re-integration but also a relief. Lately, people like Ezra Klein are busy claiming that our society gave up on progressivism not because they disagreed with the root concept, but because actual progress, outside any claims made about it on the internet, ceased to occur. If so, perhaps now is the moment to re-enter the real world, to accept that we are part of it and no amount of language or “inner work” can pry us free, and to move on from there, one step at a time on solid ground again, however doomed the journey may be.

I think there’s a great fear of “moving on” in any definitive sense, of closing one chapter and entering another. It’s the American fear of retirement—just look at Joe Biden—the fear of saying “my work here is done” and moving into whatever comes next. And yet the time to move on from the old debates of the past, the endless circular arguments over 20th century problems, the endless work of solving issues that have already been solved or that never will be, and of telling stories that have already been told, feels like it truly has come. There’s a humility to this, an acceptance that all efforts reach a terminal point eventually, but also a true and earned sense of pride, the feeling of, as Philip Roth (a rare famous man who actually retired before it was too late) put it, quoting the boxer Joe Louis, “I did the best I could with what I had.”

“Multitasking” is the opposite of moving on. It’s the process of being in the middle of all stories at once, of making no hard choices and thus ending up as far as possible from solid ground. This mindset leads to paranoia, to the feeling of not knowing what to pay attention to, what really matters, where and even what the ball we’re trying not to take our eyes off really is. Much more so than any specific conspiracy theories, the eternal, nostalgia-haunted present tense of the internet breeds a paranoid and stressed (as opposed to overworked) mindset because of this inbuilt inability to know what to pay attention to. Nothing is ever over and thus nothing truly begins. If 2025 marks an effort to return to solid ground, even as that ground further evaporates and fills with cracks, maybe it also marks the end of this paranoid mindset and the return of the ability to take things seriously, one at a time rather than all at once—having let go of all that belongs to the past in order to travel more lightly into whatever actually lies ahead. Maybe now is the time to resume the slow, hard work of fusing map and territory back together, after at least a decade during which they came wildly apart.

March 5: Trump Addresses Congress in Defiant Speech on Policy and Vision

A wild spectacle to behold, like some dead-of-night sweepstakes show on the cable access channel of a nation-sized small town in an alternate dimension. The inevitable creep of normalization is such a strange phenomenon to experience in real-time: to know how truly strange all of this is, and yet to experience that strangeness less and less intensely, until barely a vestige remains. Until strangeness is only a feeling that I know I ought to feel and yet not one I actually can.

Normalization spreads into the future as well, so that wilder and wilder possibilities seem less and less wild (what if we invade Canada? What if Trump takes a third term?), just as it also spreads into the past, where it takes on an opposite valence: what if things were never normal? What if the break that seems like it must’ve occurred in the past decade never really did?

All systems seek homeostasis, and the human conception of its place in history is apparently no different. Maybe everything’s fine?

The Democratic Party continues to attempt to force breath into the corpse of their mascot, refusing to acknowledge that it has already passed. Trump couldn’t have designed a more feckless opposition if he had a blank canvas.

What was once a two-party system has collapsed into a one-party reality, with Democrats reduced to a series of performative gestures and symbolic pageantry, pink jackets, pussy hats, rainbow flags, Kente cloths, markers of a party more focused on signifiers than addressing real concerns or change. Their identity politics reduce individuals to differences while sidestepping the material struggles shaping American life, clinging to optics as proof they are not the problem without establishing a cohesive counter-identity.

I admire that we are finally living in a mask-off moment in politics and as a nation —America was never on your side. We hardly ever look out for our own. We serve the highest bidder. We worship power. Trump plays into our ruthless nature, not as colonizers, but as heirs to manifest destiny.

“We're going to win so much, you're going to be so sick and tired of winning.” - Donald Trump

Tell that to the Democrats in Congress, fading into irrelevance before our eyes. No action, no rebuttal—just little signs, signaling a resistance that doesn’t exist, an inability to even “play dead” as James Carville recommends they do. As many former liberals can attest, it would be funny if it weren’t so pathetic.

During Biden’s presidency, they became a party of no action, watching a sitting president diminish before our eyes without even a competent PR team to dangle him as a political marionette. And his chosen successor? A president in name but not in presence, her girl-power rhetoric fading into brat summer and a vague mantra that even her most fervent supporters could never define. Time has passed, and somehow, her purpose has only grown more opaque.

They had one chance at survival with Bernie, and they shot him down twice, even though he returned to campaign for the politicians who fucked him (and seems to be doing so again now). Now, they deserve their exile. But what remains, and what’s next? If the question of the entire post-2008 era is “How do we move on from Bush and Iraq and the financial crisis?” then Obama was one possibility — “the easy way” let’s say — and Trump is another, “the hard way.” What if neither works? What if this “molten era” remains molten far longer than we imagine it could, long enough for that state to solidify?

The Spectacle of JD Vance

In ancient Egypt, pharaohs wrote themselves into eternity by rewriting the past. The stories they wanted to be remembered were carved into temple walls—propaganda turned to stone, myth disguised as memory. Across history, power has meant mastering symbols, bending reality, and encoding victory in the final word.

“This is how I win.”

The right-wing’s meme-based propaganda mirrors this ancient myth-making, using Wojaks, Soyjaks, and GigaChads as modern hieroglyphs—crude, repetitive, and stripped of craft. A visual language that doesn’t innovate but loops endlessly, distorting itself with each iteration.

Both ancient Egyptian politics and today’s media-driven environment prioritize spectacle over governance. Today’s political theater—where memes, viral moments, and symbolic gestures outweigh policy, where the shock comes not so much from recognizable ugliness as from pure incomprehensibility—mirrors this reliance on spectacle. JD Vance’s ability to surf the absurdity of his own image without losing political credibility shows that the appearance of power and acceptance of ridicule can sometimes be as effective as power itself.

I suppose there could be poetry in all this, if it weren’t so pitiful. Power now looks like a king playing a jester, stalling for a final punchline while dodging rotten tomatoes mixed with roses from the audience. Meanwhile, AI warps their image at will, feeding the machine its own vomit, ignoring the final curtain call, and stripping away another layer from an empire already gutted.

We’re witnessing a political moment in which the fragmentation of myth-making online infused with spectacle-driven governance mirrors the historical cycles of ancient Egypt - where the struggle between governance and transition defined entire eras. Whether this moment leads to a New America of consolidated power or a prolonged intermediate period of free fall remains to be seen.

A good time to reread Burroughs’ Egyptian freakout, The Western Lands.

“Desperation is the raw material of drastic change. Only those who can leave behind everything they have ever believed in can hope to escape.”

—William S. Burroughs, The Western Lands (1987)

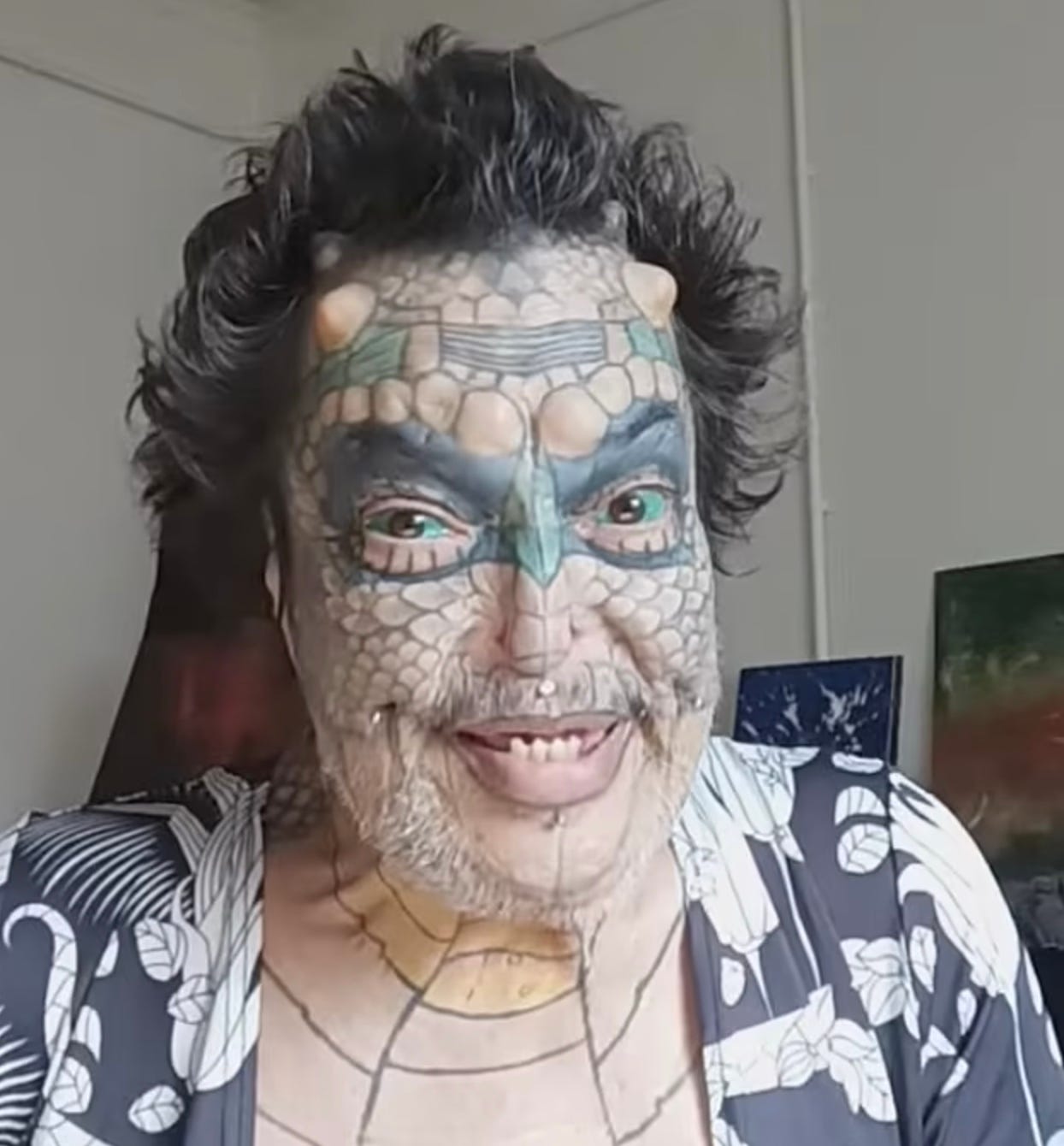

March 4: From Bank VP to Non-Binary Dragon: How an HIV Diagnosis Sparked a Radical Transformation

March 5: Scientists Create ‘Woolly Mice’ with Mammoth Traits—A Step Toward Resurrecting the Woolly Mammoth

March 7: South Carolina Man Executed by Firing Squad After Brutal Double Murder—First U.S. Execution of Its Kind in 15 Years

March 8: California Prisons Use Virtual Reality and Art to Help Inmates in Solitary Confinement Process Emotions

California prisons are introducing virtual reality as a way for inmates in solitary confinement to reconnect with their emotions and express themselves through art, offering an outlet in an otherwise dehumanizing setting. For up to four hours a day, participants immerse themselves in VR experiences ranging from everyday moments to visiting Paris or paragliding. Afterward, facilitators guide them through creative exercises—using theater techniques, poetry, painting, and other artistic methods—to help them process the feelings these experiences evoke.

2024/25: The Years of the Doppelgänger

"Year of the doppelgänger. Specifically the doppelgänger deployed as a means of gaining capital (social, financial, cultural) — to represent a world in which we must gather the most lucrative aspects of ourselves and market them as a commodity to employers, social media, etc." - @longstosee

Maybe this is why this era feels at once so alarming and so enervating, so hyper-stimulating and so boring: we’re never in one place at one time, or even in one skin at one time, anymore. We think we’re waiting for the rubber to meet the road, for the “Actual Thing” (war? apocalypse? singularity?) to occur and relieve the tension—for the story to reach a climax—but it can’t, not in the way we expect stories to, because there isn’t any one story. There can’t be another “World War” in the way we hope or fear there must be because there is no longer any one world—the atom has been split for good. The full restoration of reality—the cries to “Make Reality Real Again” and “Make Orwell Fiction Again” that issue from all sides—can’t happen because there is no coherent field in which events can take effect (which is not to say that events have no effect, but just that the relation between cause and effect has so completely broken down that it feels like a wild conspiracy theory to claim any correlation at all).

What about a future narrative form where doubles don’t look or behave alike at all? What if your double was nothing like you yet determined your fate anyway? What if you could never meet the person who was living your life?

March 13: Bonnie Blue Sparks Controversy After Seeking to ‘Bed Barely Legal Girls’ While Partying with Teenagers on Spring Break

"Look at all my shit. I got shorts in every color, I got designer t-shirts. I got Scarface on repeat. Scarface on repeat. Look at my guns. Look at my nunchucks. I got money, I got bitches… Y’all wanna see my spaceship? Spring break forever, y’all. Spring break forever."

— Spring Breakers (2012)

Much has been made lately about 2012 being a kind of “Zero Hour,” the moment when everything changed, when the simulacrum became complete, when reality “broke” or revealed its true form. This has been tied most explicitly to the mass adoption of smartphones, but perhaps there’s something more ineffable and sinister about it too (it was also the year of Sandy Hook)—the waning of the optimistic, supposedly normal Obama period and the beginning of the spread of the shadow-world that his reign led to.

With this in mind, it seems non-coincidental that Spring Breakers came out that year too—more than any other American film this century, it captured the feeling of the undercurrents beneath the present moment, the mix of gaudiness and longing and frustrated romanticism and the doomed search for transcendence through consumption, through finding a way to push the fake so far into fakeness that it becomes real again… all feelings that have only grown more overwhelming in the years since. In terms of that pure rush of being totally in-sync with the zeitgeist while revealing the deeper forces that bubble up from an unknown realm to cause that zeitgeist to feel the way it does, nothing since 2012 has come close to the level that Spring Breakers reached. That film marked the death-knell of postmodernism, of the gleeful mixing of art and trash as a known move… now those levels mix without there being any awareness that they were ever separate.

March 13: Man Charged After Allegedly Attacking Flight Attendant and Swallowing Rosary Beads

The man, Medjina Augustin, swallowed rosary beads during the incident to use as "a weapon of strength in the spiritual warfare."

He claimed he was going to Haiti to "flee religious attacks of a spiritual nature."

The flight had left from Savannah, Georgia, and was heading to Miami, Florida, but was forced to return to Savannah.

The man's sister says the outburst was justified because he "hurt anyone because he hurts evil."

The sister said the evil spirits had followed them onto the plane and they were worried about them making it to Haiti.

March 13: Texas Tech Cancels Classes Before Spring Break After Neon Green Manhole Explosions Knock Out Power

March 18: Tesla cars set on fire in the US due to Musk's policies

March 20: Massive Lightning Bolt Illuminates Atlanta Sky Amid Intense Storms and Tornadoes in Southwest USA

March 19: NASA Astronauts Sunita Williams and Butch Wilmore Greeted by Pod of Dolphins After Safe Return to Earth

March 24: US Officials Leak Yemen Attack Plans in Signal Chat Shared with The Atlantic’s Editor-in-Chief

Vance (12.13pm ET):

I will say a prayer for victory.

Waltz (13:48pm ET):

VP. Building collapsed. Had multiple positive ID. Pete, Kurilla, the IC, amazing job.

Vance (13.54 pm ET):

What?

Waltz (14.00pm ET):

Typing too fast. The first target – their top missile guy – we had positive ID of him walking into his girlfriend’s building and it’s now collapsed.

Vance (14.01pm ET):

Excellent.

Ratcliffe (14.36pm ET):

A good start.

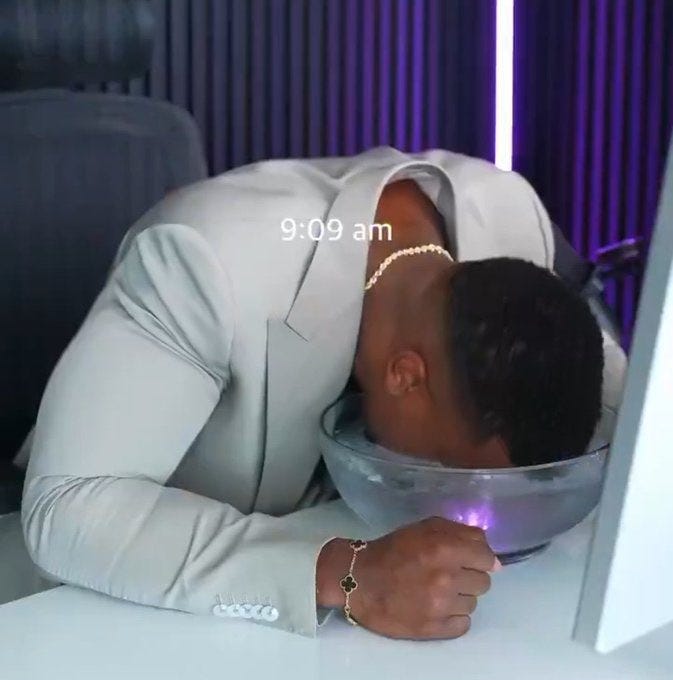

March 25: Pentagon’s Pete Hegseth, Speaking from Hawaii, Denies Leaking Secrets After Texts Reveal Plot to Kill Houthi Leader

Looking like a character from a scrapped Coen Brothers or Armando Iannucci farce, Pete Hegseth drunkenly rants at reporters in Hawaii as “SignalGate,” the dumbest and so-far most viral story of the new Trump term, spins out of control. The story of leaked “attack plans” to widely loathed Atlantic editor (and IDF prison guard) Jeffrey Goldberg is the kind of too-dumb-to-make-up story that would seem like lazy writing in a satire, yet plays as golden satire in reality. My favorite aspect of this image is the soldiers standing in the background—what’s going through their minds here? How hard are they working to keep a straight face, or are they even listening to their boss at this point?

Remains of Russian Soldier Who Died by Suicide Discovered

March 26: Wearing a $50,000 Rolex, Homeland Security Secretary Kristi Noem Visits El Salvador Mega-Prison Housing Deported Venezuelans

March 27: White House Joins ChatGPT’s Ghibli Frenzy with Meme Featuring Convicted Drug Dealer Caught by ICE

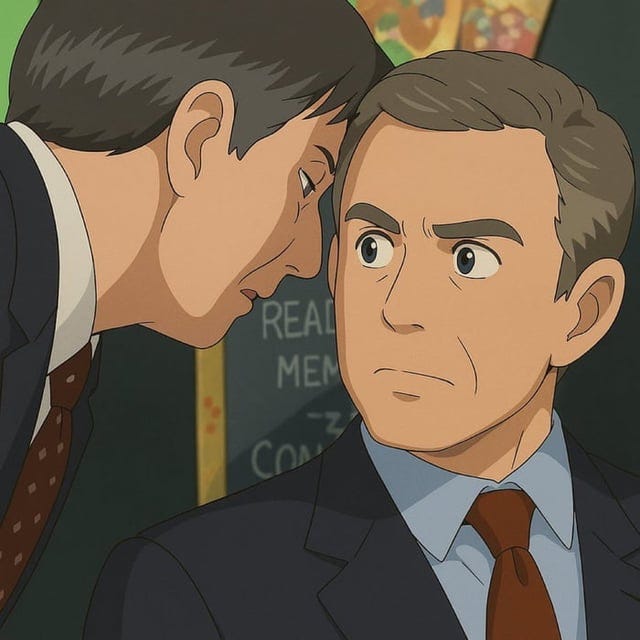

Within hours of this new visual language metastasizing across timelines, the White House jumps into the circle jerk with a Ghibli-glazed image of convicted fentanyl trafficker Virginia Basora Gonzalez being arrested by ICE. Yet again the Republicans speak directly to the hive mind. Meanwhile, Democrats are late to the party, silently screaming into a void also rendered by Studio Ghibli.

And this is just the beginning. For days, images of state violence and tragedy lacquered with a Studio Ghibli sheen clog visual channels with so much bilge our eyes go out of focus. These reimaginings flatten moral weight and artistic achievement down to kitsch, transforming both the agony of real-life violence and the rareness of artistic genius into AI slop whose ease of creation and consumption—its mindless low-key cuteness and sub-funny humorousness—smoothes over the darker facets of what it portends. Some celebrate Miyazaki’s visible disgust with how this technology bastardizes his craft, while others co-opt his style without irony, adding to the spectacle in a way that flexes no real effort to antagonize or transgress, a mass creation and consumption machine content to be part of one voice.

“Whoever creates this stuff has no idea what pain is whatsoever. I am utterly disgusted… I strongly feel that this is an insult to life itself.” - Hayao Miyazaki

It raises a profound question about the products of human imagination: do we care how and why they arise—do we need to believe they arise from anyone’s effort and inner life—or do we only care about consuming them, regardless of their source? And if it’s the latter, what purpose does this consumption serve? What will we get out of images like this, once the novelty of mass-producing them dissipates? And what will it do to our cherished memories of the actual Ghibli films, which were once such a profound part of the contemporary collective unconscious? Are we honoring these memories in a perverse yet sincere way, expressing a desire to live in a borderless, ahistorical Ghibil-verse, or are we profaning them, trashing whatever aura and sheen they’ve retained, salting the earth of sentiment and wonder and awe from which they once arose?

The flip-side: how do we relate to history, and especially to violence and tragedy, when our urge to render it into these images is so great? With a Ghibli 9/11, a Ghibli JFK assassination, and so much else, how is our relation to these moments, these “greatest hits” of our recent history, morphing?

Daniel Boorstin argued in his classic book The Image: A Guide to Pseudo-Events in America, published just a year before JFK was shot, that the 24-hour news cycle, a new phenomenon in those years, taught Americans to expect 24 hours’ worth of news every day when, in reality, only a few truly newsworthy events ever occurred in that span of time (and often there were none at all). Thus, the remaining hours filled with pseudo-events—debates, commentary, leaks, manufactured scandals, etc—to give viewers the feeling of constant news, in lieu of the real thing. Now, I perceive this addiction feeding on a much grander scale: the world is only so big, there are only so many countries and so many borders and so many factions to fight each other, just as there is only so much history, an amount that is always limited. And yet our desire for shock and drama and outrage and revelation is infinite, forcing us to resurrect the same old arguments and the same conspiracies and even the same wars again and again, doing whatever we must—even something as desperate as Ghibli-izing everything we’ve already seen—to keep the feeling of constant newness and constant emergency alive, to feel as though we’re living in extraordinary times even while living ordinary, sedentary lives.

The beautiful paradox of animation, until now, has always been that it is at once a non-human and a super-human art form. It’s a form of cinema with no people in it, where objects or drawings seem to behave autonomously, like toys when no one is playing with them, and yet the opposite is also crucially true: it is an art form in which absolutely nothing, from the the sky overhead to the grass underfoot, exists without backbreaking human labor and exquisitely honed human intention. Unlike in live-action filmmaking (and in the photos that these AI images have been generated from), where the camera catches incidental details—where you can film a man on the street without having to imagine and create the street itself—a frame of animation contains nothing except what its creators have decided and labored to put there.

What then does it mean to accept that this is no longer true and never will be again? What do we do with a superfluity of images that have no sweat or desire or fetish or limitation of any kind behind them? If we’ve already created AI to produce these images for us, how long until AI consumes them for us too? And then what?

Imagine a world in which the news is simply reported this way—where there is no original, no event to feed into the grinder, simply these images as the first and only testament to what happened. Is such a world different from the one we’re living in already?

March 23: Protests in Istanbul Emerge as Visual Nexus of Non-AI-Generated Imagery

This is all happening alongside a wave of protest images from Istanbul that resist the genre entirely—photos that no longer document but dream. A lone protester, dressed as a whirling dervish in a gas mask, stands defiantly in a haze of yellow mist like a frame from Dune. Days later, a figure in a Pikachu costume bobs through the chaos of riot police, water cannons, smoke - a weirdly haunting and magnetic image. The line between resistance and the absurd do not blur; they invert to the point where neither the real thing nor the manufactured thing is adequate. All we know is that we want more.

I can’t shake the feeling that there must’ve been a time when the absurdity of these spectacles could’ve been funny, maybe even exciting but today my thoughts always circle back to the sensation that we’re left floating in the same Interzone, where the sludge begins to feel like a cushy long-range grave. It feels like something is growing, taking shape underfoot, beneath and behind these images, and yet, at the same time, the feeling that it ever could—that anything could ever matter again in the way that things (or so we tell ourselves) once did—recedes further and further into the past.

This is perhaps the same past that all those Ghibli images are at once trying to recover and, through sheer nihilistic mockery, to bury once and for all.

“I feel that I am much more complete when I don’t understand. Not understanding, to my way of thinking, is a gift. […] It’s an odd blessing, like being insane without being crazy. It’s a gentle disinterest, a sweet silliness.”

— Clarice Lispector (February 8, 1969)